Michael. H. Glantz

October 2021

Introduction

In 2011 the Dakota Dunes, a planned community in the southeastern-most tip of South Dakota, was flooded for several summer months, with considerable property damage to the community of over 2500 people at the time. No lives were lost. The flood episode began at the end of May 2011 and ended in early September (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dakota Dunes flood. June 8, 2011. Photo: US Department of Defense

The plight of this flooded community was singled out for special attention in a New York Times (NYT) article, “In the Flood Zone, but Astonished by High Water.”1 The title suggests that the Dunes community was surprised by a so-called natural disaster that should not have been surprising at all. To read only this NYT article about this specific flooded community, one would miss the broader flood picture. It would be like “not seeing the forest for the trees.” However, the flooding of Dakota Dunes (the local destruction and misery aside) was a microcosm of what scores of communities in the Upper Midwest region went through: what they as flood victims considered to be a flood of historic dimensions.2

The flooding of the Dunes provides an example of the perceptions (and biases) of flood victims about their disastrous situation. The phrase in the NYT headline that caught my attention and sparking interest — “but astonished by high water” — that for some reason had lingered in the back of my mind ever since having read the article when it first appeared. That dormant interest was recently renewed by news articles on the flooding of the Dakota Dunes once again in 2019.

The NYT article, based on interviews with the flood-affected local Dakota Dunes residents exposed their perceptions and beliefs about the environmental risks that they willfully or unwittingly faced in the location where they chose to live — in this case, the Dakota Dunes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Google Map screenshot of the location of the Dakota Dunes community. Source: Google Maps

I re-read the 2011 NY Times article, in which I found 35 statements of local flood victims mentioned that could serve to enhance flood-related knowledge not only of the next generation of homeowners in southeastern South Dakota but of potential flood victims elsewhere. The article deepened my belief in the value of case studies and, more specifically, their potential to uncover and share up-scalable insights about individual and community perceptions and biases about foreseeable climate, water and weather-related hazards. Controversies and limitations continue about the scaling-up of local lessons drawn from case studies. Nevertheless, as an example, the Dakota Dunes inhabitants are not the only ones who now question just how reliable the notion is of a “1-in-a-100-year-flood” to the general public

Thus, the intended purpose by focusing this paper on local views about the impacts of a months-long flooding of one small community in the midst of a much larger regional flood is to show that lessons identified from floods anywhere can likely be informative to community-focused researchers and decision makers who are also concerned about flood-related disaster risk reduction elsewhere.

The case study method

When one reads a disaster-related case study about a location elsewhere around the globe, certain thoughts come to mind. For me, those thoughts centered on what I might expect to learn from a specific situation that is far away (from me) in space and time. Scientific researchers, collectively speaking, have harbored mixed “emotions” about the use and value of case studies in research, aside from addressing local community concerns. However, case studies have been successfully used for over 100 years at Harvard University as heuristic devices to educate students about legal, corporate and other business-related decision-making processes. Cases are also use in Law as well as in Business, but their value is apparently challenged by 21st century technologies and social networking.3

There are varied, often opposing, perspectives about whether the time and resources spent on such cases are worth the effort or are producing the desired educational results.4 Research by Tsang discussed the comparative advantages of case studies, arguing that “Contrary to the prevailing view that case studies are weak in generalizability, the results of case studies can be more generalizable than those of quantitative studies in several important respects [such as theoretical generalization, falsification and empirical generalization]” (p. 372)5.

Flyvbjerg’s interest in the case-study method was challenged while a graduate student: “my teachers and colleagues kept dissuading me from employing this particular research methodology. ‘You cannot generalize from a single case … and social science is about generalizing.’”6 He noted that in the late 1990s “views against case study academic research formed conventional wisdom about case-study research.” I had a similar experience in the 1960s-80s as a grad student and, later, as a postdoc at a national science center, when I was asked by the center’s director when I would generalize my findings from various social science cases I had been researching. Caught by surprise by such a question, I responded, “I guess I’ll be able to generalize when I have researched and read enough case studies.”

Flyvbjerg (p. 219) identified and challenged five common misunderstandings about the use of case studies in social science research.

- Theoretical knowledge is more valuable than practical knowledge.

- One cannot generalize from a single case study. Therefore, the single-case study cannot contribute to scientific development.

- The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypothesis testing and theory building.

- The case study contains a bias toward verification.

- It is often difficult to summarize specific case studies.

He addressed each of these statements in depth citing other researchers, ending with a convincing argument in favor of the use of case studies for knowledge generation and for decision making. He concluded with a comment by Thomas Kuhn on the importance of cases for the social sciences: “A scientific discipline without a large number of thoroughly executed case studies is a discipline without systematic production of exemplars, and a discipline without exemplars is an ineffective one.”

There are pros and cons about each research method, and that is true as well for case-study methods. This paper is not focused on the debate about the value of case studies to policy making. The author hopes to make readers aware of how a study of a specific flood in a specific place at some previous time or place may provide lessons to prepare for and cope with possible hydrometeorological threats in the future.

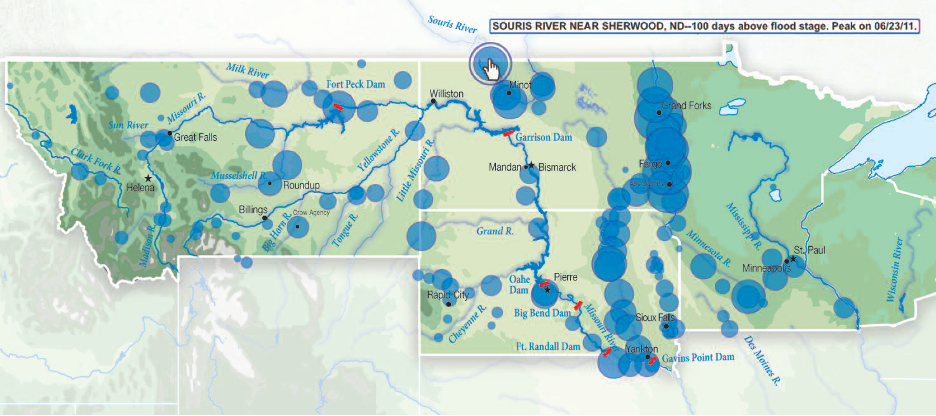

Regional US Midwest 2011 flood setting

An overview of the regional floods of 2011 in the Upper Midwest was provided in the Fedgazette, a publication of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Its editor referred to the regional flood as “a flood of floods.”2 He wrote his review in October of the flood year, “The floods of 2011 were historical in breadth, volume and duration, particularly in the Dakotas and Montana.” He then suggested that “As such, the floods of 2011 can be hard to appreciate as a headline news story. They were so widespread, so huge in volume and so long in duration that they read more like a novel in their scale” (Figure 3).

Figure 3. “Streamgage readings suggest a sense of scale of 2011 flooding.” Source: Fedgazette, 2011.

The Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) was responsible for managing water flow from major rivers in the region such as the Missouri and the Big Sioux. It is responsible for water releases and for levee construction and maintenance. As reservoirs and dams along the Missouri River and other feeder rivers filled to capacity, the Army Corps was forced to release large flows that flooded to varying degrees downstream communities, including the Dakota Dunes.

Wirtz also noted that the Corps helped with sandbagging activities as did the National Guard to protect specific structures and infrastructure. He wrote that “No single location probably benefitted more from the Army Corps levees than Dakota Dunes, S.D., a town of 2,500 situated a stone’s throw from Nebraska and Iowa in the southeastern corner of the state. About 460 homes in this upscale bedroom community would have filled to the rafters without a massive, four-mile levee built over the course of about a week in June.”

Fast forward to 2016

In 2016, the fifth anniversary of the Dakota Dunes’ flooding, South Dakota reporters used the occasion to revisit the flood episode of the Dunes, reviewing causes of and responses to it. The Yankton Daily Press and Dakotan for example, reminded readers that “The flood arose [in 2011] from large Rocky Mountain snowpack combined with record Great Plains rainfall.”7 As a result of such large volumes of water, the Army Corps of Engineers released water from behind dams in a controlled manner which consequently led to flooding the Dunes and other places in the region. The two major rivers — the Missouri and the Big Sioux —surpassed their flood stages. The cost of the Missouri River flooding of the Midwest was estimated at $580 million.

The inhabitants of the Dunes had been warned by the Army Corps of Engineers that they might have to evacuate on short notice (a few hours) and to prepare for that possibility. “About half the community evacuated [about 1600 people], and the other half stayed here.” Dockendorf highlighted the contribution of the National Guard in sandbagging for levees and that federal to local officials and affected residents worked well together8 (Figure 4). Dockendorf concluded with the following:

Once the flood receded, the levees were removed and the evacuation was lifted …. [M]any homeowners faced massive cleanup or the possibility of rebuilding their homes. But nearly all families returned and resolved to keep Dakota Dunes and surroundings as their home.

Figure 4. Constructing Sandbag levees. Source: S.D. National Guard. 2011.

Since 2011, the Army Corp of Engineers worked on revising the region’s flood risk maps. In the updated 2019 flood-risk map, the 2011 flood zone (originally designating a 1-in-100-year occurrence) was reassessed and recalculated. As a result, the new map had repositioned the Dunes into the 1-in-500-year flood zone.

Fast Forward again to 2019

In the Spring of 2019 residents of the Dakota Dunes, once again, faced flood alerts. As iGrow noted in mid-March “Dakota Dunes flooding concerns intensify,” with the scary subtitle “Concerns about a repeat of 2011’s flooding.”9 This time major focus was on the Big Sioux River flow, the elevation of which was approaching flood stage by topping riverbanks. The Missouri was a concern as well: “Dakota Dunes worried about possible flooding from the Missouri River.” Dockter reported in the Sioux City Journal at the end of May on the status of the rivers threatening the Dunes:

As the swollen Missouri and Big Sioux rivers neared their high points, anxious Dakota Dunes residents prepared to leave their homes for up to five days, until the floodwaters receded….If the Missouri reaches a depth of 31 feet or more, authorities said they would order an evacuation of all Dakota Dunes neighborhoods….If the water breaches the communities’ flood barriers, an immediate evacuation notice would be issued.10

In September of this year the Dakota Free Press presented a blog entitled “Facing Flooding Again, Dakota Dunes Orders Everyone Out” about the months-long threat of flooding to southeastern South Dakota.11 Heidelberger’s blog touched on the local concerns that had been sparked by the likelihood of severe flooding in the region for the third time in this year . Specifically, he opened his blog with the following: “Once again, the country club set is surprised that building McMansions in the flood plain means McMansions get flooded.” An anonymous reader, Noelle, responded to the discussion that followed the blog:

“Some of you may not remember, but before the dams went in on the Missouri there used to be “Spring Flooding” almost every spring. That is why the “Dunes” are called the “Dunes”!! Just because people decided to build “Expensive Homes” there doesn’t mean the river is going to treat them any different. The dams can only control so much water as it comes down the river…flooding happens “up river” as well as “down river” and the water has to go somewhere! Water flows into the Missouri below the dams also, and no one controls that.”

Heidelberger ended his blog with the following advice:

“Floodwaters challenging a community’s dikes three times in one year and prompting a total evacuation is certainly bad… but when it keeps happening, [NB: a reference to the 2011 flooding] maybe it’s time to stop raising levees and instead raze some houses and get out for good.”

After September 2019 threateningly high-water levels in the two major rivers, the Sioux and the Missouri, began to slowly drop, attention shifted to concern about flood possibilities in the following year, 2020. The Army Corps of Engineers announced a plan for releases of water from dams to make room for expected snow melt and higher seasonal precipitation than average over the winter into 2020. It was also concerned that soils, heavily saturated from a record-breaking regional rainfall in 2019 (“wettest 12-month period in 121 years of record keeping,”) would be unable to retain water with precipitation in the Spring 2020. For regional water managers, it became a life-threatening/lifesaving juggling act involving the volume and timing of water impoundment, water releases from dams and the calling for evacuation from flood-prone parts of The Dunes community. 12

The Flooding of the Dakota Dunes in 2011

The 2011 Dakota Dunes case study is based on highlighting and then clustering flood victims’ comments and commentary in the New York Times article into the following categories: (1) Earliest Warnings; (2) Blind Faith in Technology and Engineering; (3) Misunderstandings; (4) Misperceptions; (5) Risk Categories; (6) Tradeoffs; and (7) Blame Game. Some comments could have been placed into more than one category.

The Dakota Dunes is an unincorporated Master Planned Community in the southeastern-most corner of the US State of South Dakota, located at the confluence of the Missouri and the Big Sioux rivers. Its population is just below 3000. The Dunes was a master-planned community designed in 1988 and owned and operated by Berkshire Hathaway Energy in Des Moines, Iowa.13

According to Bankrate.com,

A master-planned community is a large-scale residential neighborhood with a large number of recreational and commercial amenities, such as golf courses, tennis courts, lakes, parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and even stores and restaurants. Some master-planned communities may have schools, office parks, large shopping centers and other businesses.

The average master-planned community is more than 2,500 acres and located in an urban or suburban environment. Residents move there to experience a self-contained environment. All social and recreational opportunities typically are limited to residents and their guests.14

In any given year numerous communities in the US as well as around the globe are likely to suffer from flooding, because of heavy rains during severe thunderstorms or tidal surges in coastal areas during hurricanes or tropical storms. Inland riverside communities are subjected to flooding, because of heavy rains upstream in a water catchment area. There are also controlled floods as well. When dams and reservoirs reach levels close to capacity and heavy rains are expected to continue, water managers are forced to make difficult decisions: let the excess water over-top the dams and reservoirs with unmanaged impacts downstream or plan to release water from them to make room for the expected surplus water. Controlled water releases cause flooding downstream but allow the water managers to alert downstream communities to prepare in situ or evacuate.

Victims’ perceptions about the 2011 Flooding

In the sections that follow, the comments in italicized blue font are taken verbatim from Sulzberger’s NYT article interviews and commentary.

When a new real estate development project is proposed, there are community members who oppose it. People in general do not easily embrace the “ordeal of change,” especially when change is proposed by outsiders to that community.15 In the case of the Dakota Dunes Master-Planned Community, some area residents argued against it for a variety of reasons. For example,

“Some skeptical locals offered a warning when developers transformed this most barren peninsula in South Dakota’s extreme southeast corner at the intersection of two rivers into an exclusive planned community.”

Those who contested the proposed housing development were branded in negative ways by its supporters in order to minimize their objections, in spite of the environmental signs that they felt put the development in a precarious position given its topography, e.g. the sand buildup of sediments over time of the two converging major rivers. Existing warning signs for potential flooding were discounted by developers and by potential residents as well.

- Earliest Warnings

Other examples of the earliest warning include the following:

- “Many people in these higher-risk areas mistakenly believed that a flood could not happen more than once a century — the areas are called hundred-year flood zones, based on the calculation of an annual 1 percent chance of flood. Those outside [the zone] often falsely believe that they are not at risk, even though they account for about a quarter of all flood insurance claims.”

- “As the years passed, those who dismissed a flood as unlikely started talking about it almost as an impossibility. Most residence had dropped their flood insurance.”

- “Even [in 2011] when the Army Corps of Engineers began reporting record snow and rain would force unprecedented water releases from reservoirs for most of the summer, some residents considered the warnings overstated.”

Sulzberger noted that misperceptions carried over to questioning scientific research and consensus about the foreseeable consequences of a changing climate.

“[Even] as many experts warn that climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of flooding and other natural disasters, developers continue to build homes in flood-prone areas.”

Sulzberger recorded the following sign of awareness of the foreseeability of flooding:

‘“Older communities, when they were being settled, learned through trial and error where to build — that’s why Sioux City is established on higher ground,’ said … the city manager. ‘It’s only in recent decades that you’ve seen development in the lower areas like the Dunes.’”

- Blind Faith in Technology and Engineering

The developers of the Dunes pointed out to prospective home buyers the technological and engineering fixes that had been put in place to protect settlements along the two major rivers and for the sandy peninsula that had built up over a long time from the rivers’ sediment deposits. Dams, reservoirs and levees were viewed as technological fixes that were going to protect the planned development of the Dunes. Some victims of the 2011 flood said that they had no idea there was a flood risk, given the various engineering activities to control the river flow and the fact that there had not been a flood for the 10-year period since the development had been completed.

They assume that if there is some level of protection like a levee or an upstream dam, they’re safe. As a general rule, public officials don’t like to dissuade them of that fact.

Fostering the belief that technology and engineering would “save” them from harm led to a false sense of security (e.g. letting one’s guard down). And, if tech and engineering fail, the government would backstop them, or so they thought.

Others at the Dunes believed that the two rivers that converged and formed the sandy dunes area had been tamed. “A few [home buyers] even paid a premium to be closest to the flowing water of the Missouri and the Big Sioux.” Those who may have considered a risk to flooding downplayed warnings and warning signs about foreseeable flooding, because they selectively chose not to pay attention to information they did not want to believe, e.g. “selective inattention”.

Marketing hype for potential buyers that included information that the Dakota Dunes was safe contributed to the community’s lowering its guard and fostered a false belief that flooding was not a threat and that flood insurance would not be necessary.

Though developers initially urged residents to get insurance, they noted that the Missouri had been successfully controlled since the dam system was built.

As for the Big Sioux River,

After about a decade, concerns about the less predictable Big Sioux prompted the construction of a levee, which led the government to reduce the flood risk for another 160 lots — removing the flood insurance requirement and making them easier to sell.

The bottom line is that the government knew that the technological engineering fixes to control river flow had their foreseeable limitations. However,

inhabitants assume[d] that if there is some level of protection like a levee or an upstream dam, they’re safe. As a general rule, public officials don’t like to dissuade them of that fact.

This chain of events could be seen as a “cascade of misperceptions,” that is, misperceptions that lead to other misperceptions such as the offering of flood insurance that people do not really want to pay for and, later, dropping any mention of it, likely making the property easier to sell with no reference to flood potential. This cascade was reinforced by government statements as well as by expectations about the safety provided by dams, reservoirs and levees. The cascade was apparently reinforced by a lack of understanding of rivers and of probabilistic information (e.g. the 20-year period of the Dunes’ existence with no flooding was not a reliable indicator of no flooding in the future). The bottom line is that “they never imagined this chain of events.”

- Misunderstandings

Well known in the science community about flood probability is that

Most people don’t understand what flood risk is,” said … a civil engineering professor at the University of Maryland who has written extensively about his concerns…. They assume that if there is some level of protection, like a levee or an upstream dam, they are safe.

The simple and straight forward concept of a “1-in-a-100-year flood” is confusing to some people and misleading to many others. What it means is that each year there is a 1% chance of flooding. It does not mean is that once you have had a flood you will not have another one for 99 years. Nevertheless,

“Many people in these higher-risk areas mistakenly believed that a flood could not happen more than once a century — the areas are called hundred-year flood zones, based on the calculation of an annual 1 percent chance of flooding.”

Sulzberger went on to write,

“As the years passed, those who dismissed a flood as unlikely started talking about it almost as an impossibility.” [In 2011] “newly built levees strain to keep this community from surrendering to a historic flood.”

It seems pretty obvious even to the casual reader that a more effective, user-friendly way is needed by the scientific community to convey to the general public flood-plain-related probability statements. In fact, Meyer and Kunreuther16 citing Weinstein et al.17, noted one such a way,

If a homeowner is considering flood protection over the 25-year life of a home, she is far more likely to take the risk seriously if told that the chance of at least one severe flood occurring during this time period is greater than 1 in 5, rather than 1 in 100 in any given year. Framing the probability using a longer time horizon should be attractive to insurers and real estate agents who want to encourage their clients to invest in protective measures. Likewise, people may be better able to evaluate low-probability risks if they are described in terms of a familiar concrete context.

- Misperceptions

Perceptions influence behavior and erroneous perceptions can have societal consequences. Different people can see the same object and come up with different descriptions about its characteristics (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Perception is everything. Source: Anon.

People look at nature differently: some say live with it, while others want to change it to meet contemporary needs or wants. Some people look at the future in a similar way. For example, some people do not care about future generations. Some discount the future, by favoring to take short-term benefits now as opposed to foregoing them now in the hope of reaping greater benefits in the future. There is also a tendency to discount the past, suggesting that the past is really not a reliable guide to the future. For example, some argue that a changing climate makes the use in decision making of past history of extremes of climate, water and weather in a given place less reliable as a predictor of the future.

Some inhabitants of the Dunes refused to support community efforts for building levees, because of the following: their perception of the meaning of a 1-in-a-100-year flood; their expectation that dams tame rivers; and that there had been no flood threats in the past 20 years (the lifetime of the Dunes).

“Homeowners typically dropped the insurance after several dry years, and by the time of the 2011 flood, only 172 homes in the entire county now carry it.”

As noted, 20 years is too short and unrepresentative as a period of time to rely on for assessing flood-related threats. Here, the 1922 Colorado River Compact can serve as a useful lesson. Negotiators for the river compact in the early 1920s relied only on the previous 2 decades of rainfall and streamflow records (1900-1920). These two decades turned out to be a very wet 2-decade anomaly in rainfall and streamflow, even though longer historical records existed showing the occurrence of severe decades-long droughts. As soon as the inked signatures of the 7 state representatives went dry, Colorado River flow began to decline to the political advantage of the lower Colorado River Basin states.18

Dam construction, however, relies on longer historical records to capture decadal-scale rainfall and temperature fluctuations.

“Much like the developers, the new residents were not worried.”

- “This community has been here over 20 years and never had a problem,” he said. “I didn’t think it [flooding] was an issue.”

- “And now [2011], some people are using the high waters from North Dakota to New Orleans to revisit longstanding questions about whether the very government programs designed to safeguard people from floods, including protective measures like dams and levees and recovery programs like flood insurance and disaster assistance, actually encourage them to take unnecessary chances.”

- “Scott Mackie, like most of his neighbors, did not take out flood insurance on his newly built house — not because he could not afford it, he said, but because he believed the Missouri had been tamed by a system of dams and reservoirs.” “Many residents here in the southeastern tip of the state … say they never imagined this chain of events.”

- Risk Categories

Perceptions vary about the level of risk for the same hydromet hazard. People can be risk adverse (cautious), can be risk takers (gamblers), risk-ignorant (just plain unaware of the hazards in their new situation or location) or risk ignore-ant (they know the risks, but they think they are clever enough to avoid problems). “Willful disbelief,” a sign of being “risk ignore-ant,” refers to a person who is aware of and understands the risks based on data choosing to ignore it. This person does not seriously consider facts that may not conform with his/her beliefs. This risk category differs from “risk ignorance,” which refers to someone who does not understand the risks s/he faces where s/he lives or works.

Yet another neglected unnamed risk category, the risk maker. It refers to a person or organization whose decisions put others at risk but not the decision maker. If the decision has negative outcomes, the decision maker may suffer relatively little to no loss, whereas those his decisions had put in harm’s way do the suffering. While those harmed are dealing with the adverse consequences of those decisions, the risk maker returns to the office to develop different decisions.

- Trade-offs

People make trade-offs knowing risks they may face in the future but they tend to discount the possibility of those risks directly affecting them. Some people will embrace the risks, while others will tend to avoid them.

There are signs in the Dunes case where people (human nature) were ready to take on Mother Nature by continuing to live in the same now-flooded location in the future. For a variety of reasons, they choose to stay in the flood-prone Dunes: Some misunderstood 1-in-a-100-year flood probability, assuming that they were free from flood for the next 99 years; Others said that there were risks everywhere and they did not know them but now they know the risk they face if they stay. Sulzberger reported the following comments related to risk tradeoffs.

- “If I had to do it all over, I’d still purchase the same lot” Mr. Rounds said. “I really do think it’s an aberration.”

- “Absolutely we’re going to stay,” Tim Boyle said as he stood in his emptied house. He detailed some of the charms of river life: the bald eagles nesting on the cottonwood trees, the boat rides searching for catfish and walleye, and the summer parties on the dunes out front. And no, he was not worried about another flood.”

Perhaps the most telling perception about trade off on risks is the following:

His wife, Debbie, cut in. “There’s risk everywhere,” she said. “There’s risk in Arizona for fires, in Florida for hurricanes, in California for earthquakes.”

- The Blame Game

“Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan.” “When something goes wrong people look outward for someone else to blame: ACE, realtors, developers, mother nature – but seldom point inward at themselves for misperceptions or not having done their homework about rules in their new settlements.” As the shock of flood impacts began to wear off, flood victims in the Dunes began to look for someone or some agency to blame for their losses. Former South Dakota Governor Rounds, “[l]ike many residents in the state, he believes the flood is largely the result of mismanagement by the Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dams.” [NB: The Corps had warned the Dunes inhabitants that the releases were forced by unprecedented snow and rains.]

Sulzberger captured the sentiment of another flood victim who raised concern about equity:

- Down the road at Riv-R Land Estates, Tom … looked at the rows of houses protruding from the widened river. Upset that more money and effort was focused on protecting the much larger and wealthier Dakota Dunes.

- I don’t want it to seem like we’re looking for a handout,” he said. “Since we didn’t get the support that some of the other communities got on the front end, it would be nice to get some support on the back end.

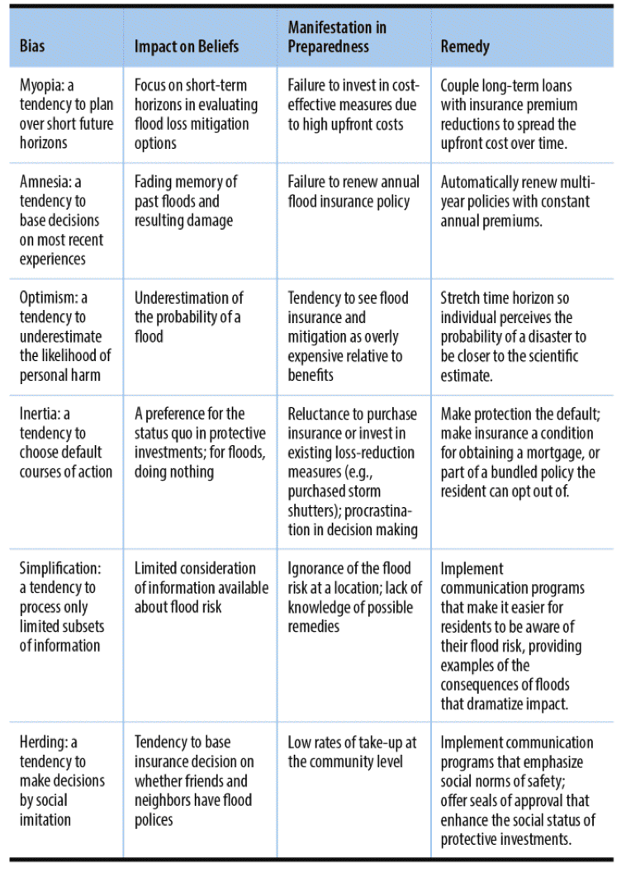

Considering the framework of the “Ostriches Paradox” for the 2011 Dakota Dunes flooding

This section was prepared after the paper had already been written and before I read the book by Meyer and Kunreuther “Ostrich Paradox.”16 I found their framework (Figure 6) of bias categories by people related to behavioral risk to be very informative and added these few paragraphs to the Dakota Dunes flood paper. The authors, experts in risk assessment, have identified biases that influence individual as well as community decision making in the face of hydrological and other threats. They categorized risk—related behavioral biases.

Figure 6. Behavioral Risk Audit Problem – Solution Matrix for Reducing Future Flood Loses. Source: Meyer and Kunreuther (2017, Table 9.1).

Like many readers of the original New York Times article1 or similar news reports of community flooding, the “Ostrich Paradox” can provide a framework for readers’ mental take-away messages from a case study of a flood in a community. The book has widespread value to an enhanced understanding about behavioral responses to flood-related risks and responses to them in communities and governments around the globe.

Their framework can be used to assess responses to the Dunes floods using the following psychological categories biases proposed by Meyer and Kunreuther: (1) Myopia; (2) Amnesia; (3) Optimism; (4) Inertia; (5) Simplification; (6) Herding.

- Myopia bias is defined in this context as “a tendency to plan over short future horizons.”

- This relates to discounting consideration of the future costs and benefits by focusing instead on short term gains.

- Amnesia bias is defined as “a tendency to base decisions on most recent experiences.”

- This relates to discounting consideration of the past and focusing on recent times. The absence of a flood since the Dakota Dunes development project was just an idea a couple of decades before the 2011 flood episode.

- Optimism bias is defined as “a tendency to underestimate the likelihood of personal harm.

- This relates to a general feature of human responses to the threat from potential hydrologic and other hazards. Bad things happen to others in the face of a flood hazard. “They believe they are more immune to threats than others.”

- Inertia bias is defined as “a tendency to choose default courses of action.”

- It is the option to do nothing, not act. Inaction is a form of action: too many options, remaining uncertainties, cost of acting, “wishful thinking” that the victim is usually the proverbial other guy.

- Simplification bias is defined as “a tendency to process only limited subsets of information.”

- This behavioral aspect of coping with flood-related risk come from ignorance (being unaware or uninterested in knowing more about such risks in a given location) or from “ignore-ance” (being aware of flood risk information but just not caring about it).

- Herding bias is defined as “a tendency to make decisions by social imitation.”

- Meyer and Kunreuther succinctly noted “It is the tendency to base insurance decisions on whether friends and neighbors have flood policies.” This is similar to a “crowd mentality.”

Their original chart, in the appendix, is a useful reminder of biases that cause people to make the decisions they do when their life, livelihood and property are threatened by hydro-meteorological and other hazards.

It is important to note that each of these biases does not exist in isolation but may be influenced by other behavioral biases noted by Meyer and Kunreuther, such as an anchoring bias, a compounding bias, an availability bias, a single-action bias, a status-quo bias and a perceptual bias. Multiple biases can be at play in a threatening flood situation.

Concluding thoughts

There are various ways to summarize the “lessons” from the Dunes about how to cope with the obstacles to hazard preparedness and disaster readiness. For example, there are general aspects that directly affect victims’ perceptions and influence the actions they might take based on their perceptions. Such observations as the following might prove to be similar to those found in other hydro-meteorological case studies: misperceptions about hazards; poor public understanding of probability; poor understanding of risk; distrust of science; distrust of institutions; blind faith in tech and engineering solutions; mistrust of “scientific” information. Specific observations drawn from the Dunes case could also apply to lessons identified in other climate, water and weather-related cases. Some examples are the following:

- Risk maps are 2-edged swords.

It is good to know about the risks that exist in the place where you choose to live. Risk maps help home buyers to do that. However, for those who do not understand flood risk (e.g. one in a hundred-year flood), a flood risk map may provide a prospective homeowner a false sense of security.

- Developers are relentless in developing properties for sale.

Potential buyers of properties have a responsibility to be aware of the motives and motivations of the developers’ representatives.

- People tend to “discount the past.

Many people have come to believe that societies, technologies have progressed so far and so fast that historical information becomes increasingly less useful as each year goes by.

- People have short attention spans.

Decades ago, way before the iPhone and the Internet, it was estimated that in the USA, the public’s attention span was estimated at 2.3 years.19 Given social networks and rapid (if not instant) communications o. That attention span has surely become drastically shortened, another pressure against the use of the past for decision making in the future.

- People engage in “selective inattention.”

People have mental models of how they believe the world around them works. New information must fit in that preconceived model. If that information challenges their beliefs, they will discard it.

- Government disaster programs can encourage disasters.

Governments do not often deliver on their pledges.

- Technological fixes are seen as “cure-all” solutions;

People “pick their poison” in that they choose to settle in regions with known hazards but they may not know the risks associated with those hazards. Another expression that comes to mind is “the devil you know.” People make choices about risks and, in this case, they often choose to stay with the risks they know and perhaps with the idea to identify better ways to cope with that devil as opposed to moving elsewhere and having to cope with risks they don’t know.

Quick Summary

- (Mis)perceptions are abundant

- Maybe the better word to use is “mixed” perceptions. Also, “do not believe everything you think.”

- The “Risk Map” Problem

- A risk map is one of the earliest warnings to land developers, sellers and buyers. How should they be described to the public?

- Do not rely only on governments

- except in a disaster?

- People do not understand probabilities

- Replace probability statements with “foreseeability” statements.

- Human timeframe is out of phase with environmental and climate variabilities and changes

- We think in terms of a few decades at the most. Nature doesn’t think.

- There a distrust of science … but a “blind faith” in technology

- Consider the value of instituting “Social Inventions” (words, concepts, slogans) to change perceptions and behavior (to match them with reality)

Every hydrometeorological hazard and disaster report has its lessons identified (misleadingly considered learned) and recommendations for future responses to similar threats. The case studies are surely of value to those in the case-study community. They likely have value in some aspects to other communities directly or indirectly. For example, lessons identified, and recommendations made should be accompanied by a statement of the ramifications if the identified lessons are not tested for reliability and if their recommendations are not implemented.

References

- A. Sulzberger, “In the Flood Zone but Astonished by High Water,” New York Times. 31 July, 2011.

- Wirtz, R. A., 2011. “A Flood of Floods.” FedGazette: Regional Business & Economics Newspaper, Vol 25, No. 4. (October). https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/files/pubs/fedgaz/11-10/fedgazette_flood_of_floods.pdf

- H. Murray, J. M. Lanicci and J. D. Ramsay, “Environmental Security: Concepts, challenges, and case studies” (University of Chicago Press Books, 2019). https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/E/bo40058637.html

- Heskett, J. L., 2019. “Has the Twitter Age Left the Case Method Behind?” Harvard Business School, Working Knowledge (August 1). https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/has-the-twitter-age-left-the-case-method-behind

- Tsang, E.W. K., 2014. “Generalizing from research Findings: The Merits of Case Studies,” International Journal of Management Reviews. Vol.16, pp. 369-383.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2006. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Sage Journals: Qualitative Inquiries. April, Vol. 12, Issue 2. p. 219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Dockendorf, R., 2016a. “Five years later: Dakota Dunes officials look back on devastating flood.” Argus Leader (June 24).

- Dockendorf, R., 2016b. “Recovery of The Dunes: Dakota Dunes Officials Look Back On Devastating Flood.” The Yankton Daily Press and Dakotan (June 15).

- iGrow 2019. “Dakota Dunes flooding concerns intensify. Concerns about a repeat of 2011’s flooding.” (March 14)

- Dockter, M., 2019. “Dakota Dunes prepares to evacuate as Missouri River nears crest; metro area streets flood,” Sioux City Journal (May 31).

- Heidelberger, C.A., 2019. “Facing Flooding Again, Dakota Dunes Orders Everyone Out.” Dakota Free Press.

- Hytrek, N., 2019. “Conditions ripe for Missouri River flooding in 2020 (October 23). https://siouxcityjournal.com/news/local/conditions-ripe-for-missouri-river-flooding-in/article_1680944d-e910-5f98-9db2-221608ca6ec6.html

- Wikipedia, 2019. “Dakota Dunes.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakota_Dunes,_South_Dakota (Last edited July 14).

- com. https://www.bankrate.com/glossary/m/master-planned-community/

- Hoffer, E., 1952. Ordeal of Change. Harper & Row.

- Meyer, R. and H. Kunreuther, 2017. The Ostrich Paradox: Why we underprepare for disasters. (Philadelphia, Pa: The Wharton Press; ebook version, Apple Press).

- Weinstein, N.D. K. Kolb and B.D. Goldstein, 1996: “Using Time Intervals Between Expected Events to Communicate Risk Magnitudes,” Risk Analysis 16, no. 3. 305-308.

- G. Brown, “Climate Variability and the Colorado River Compact: Implications for Responding to Climate Change,”in M.H. Glantz, Societal Responses to Regional Climatic Change: Forecasting by Analogy. (Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1988) 279-305.

- Downs, “Up and Down with Ecology: The ‘Issue-Attention’ Cycle.” The Public Interest, 28: 38–50. 1972